A Rural Water Innovation and its Ripple Effect: Informal Water Operators Ready to Embrace Clean Water

Bono and Ahafo Region, Ghana — What happens when the paradigm changes from “water is life” to “safe water is life?” Although subtle, the shift toward ensuring the safety and quality of drinking water supplies has implications for viability of water operators and the potential for wide-ranging public health benefits. This is particularly true in rural areas, which frequently lack the resources and expertise to monitor water quality compared to their urban counterparts.

One way USAID is helping to bridge the urban-rural divide is through the Water Quality Assurance Fund, which incentivizes established urban laboratories to provide water quality testing services to rural water systems by guaranteeing consistent and reliable payments for testing services. This innovative payment guarantee allows established laboratories to provide smaller systems with the information they need to maintain safe water quality standards.

Potential benefits* of regular water testing:

- Increased public awareness of safe water practices

- Improved adoption of chlorination practices

- Increased revenue for water systems and laboratories

- Stronger ownership among water operators (via a heightened sense of responsibility, commitment, and control)

*As described by local stakeholders

USAID’s REAL-Water (Rural Evidence and Learning for Water) program is evaluating this financial innovation in Ghana and Kenya with plans to also pilot it in Uganda and Tanzania. In Ghana, where the Assurance Fund was initially piloted, 34 rural water systems across 11 districts of the Bono and Ahafo regions are now enrolled in the Assurance Fund evaluation.

An Increased Focus on Informal Water Suppliers

The Assurance Fund evaluation’s early findings suggest that informal water suppliers are a much bigger part of the water supply landscape than initially thought, serving up to a quarter of the population of communities in the Bono and Ahafo regions of Ghana. While the existence of informal water suppliers is well-documented in urban areas, their prevalence in rural settings is poorly understood in Ghana

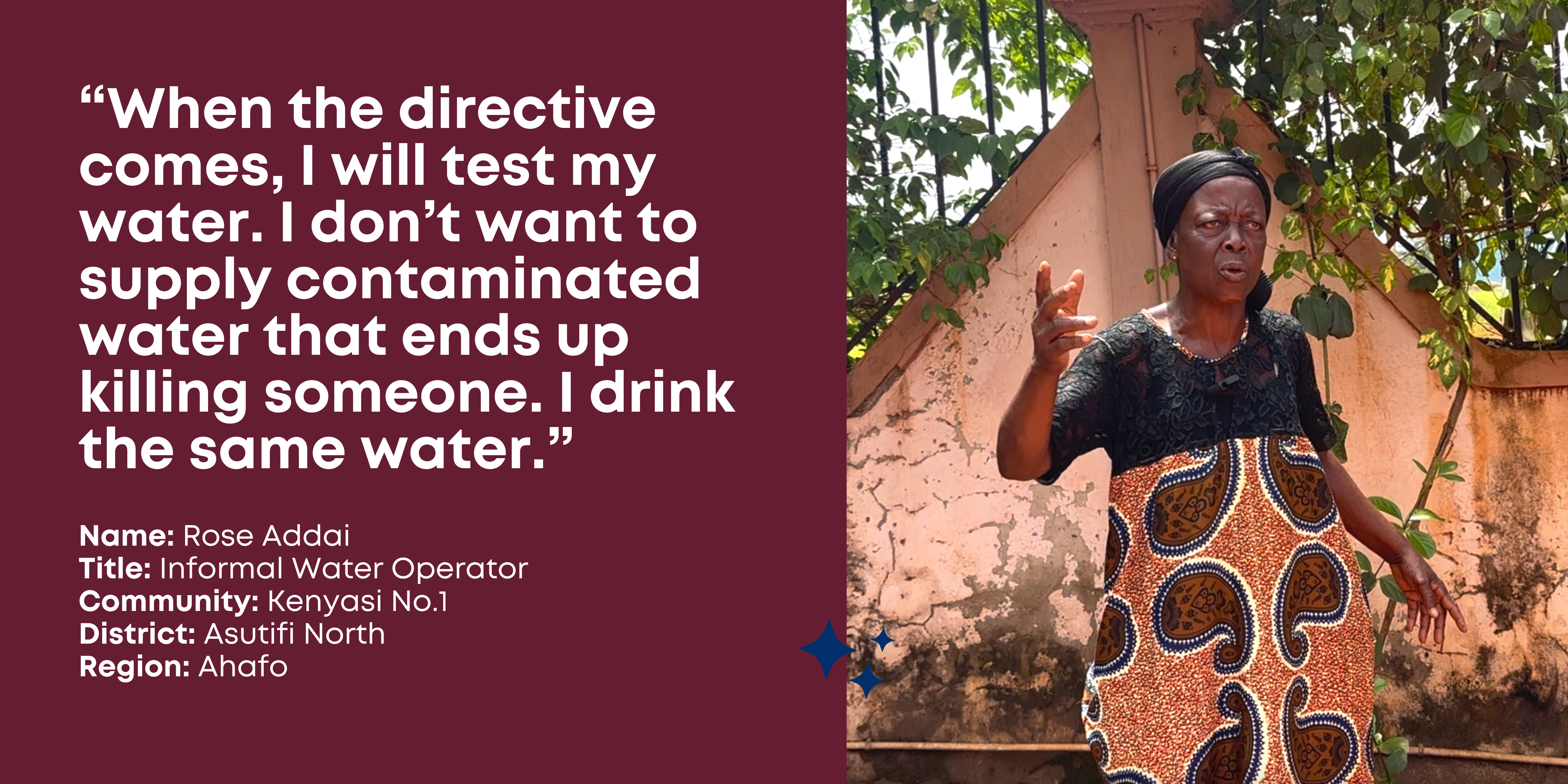

These informal providers are typically entrepreneurs who pay out-of-pocket for the drilling and mechanization of boreholes and then sell water to local customers. The informal operators are unregulated, leading to uncertainties about water quality for consumers and a lack of standardized treatment procedures.

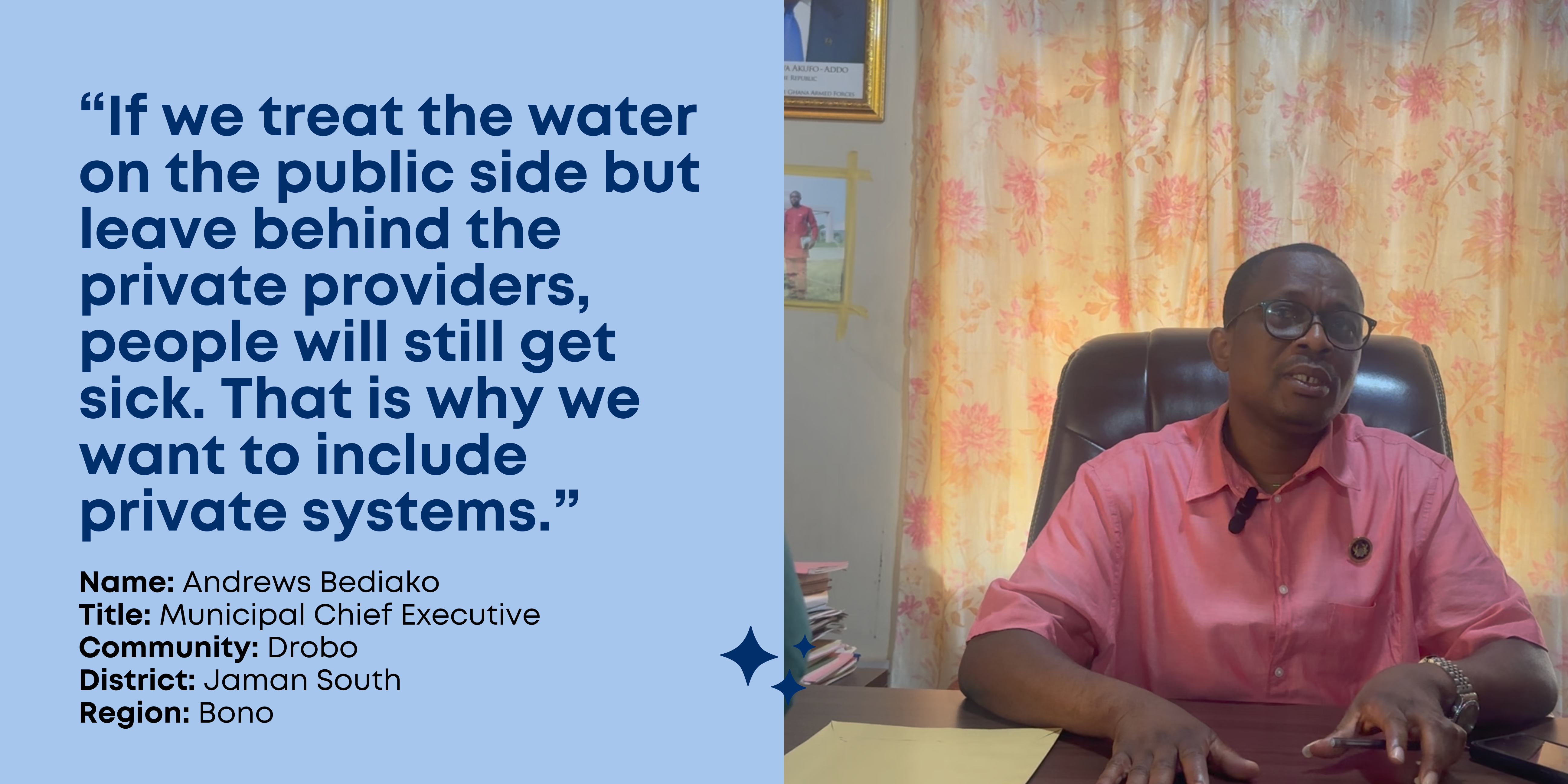

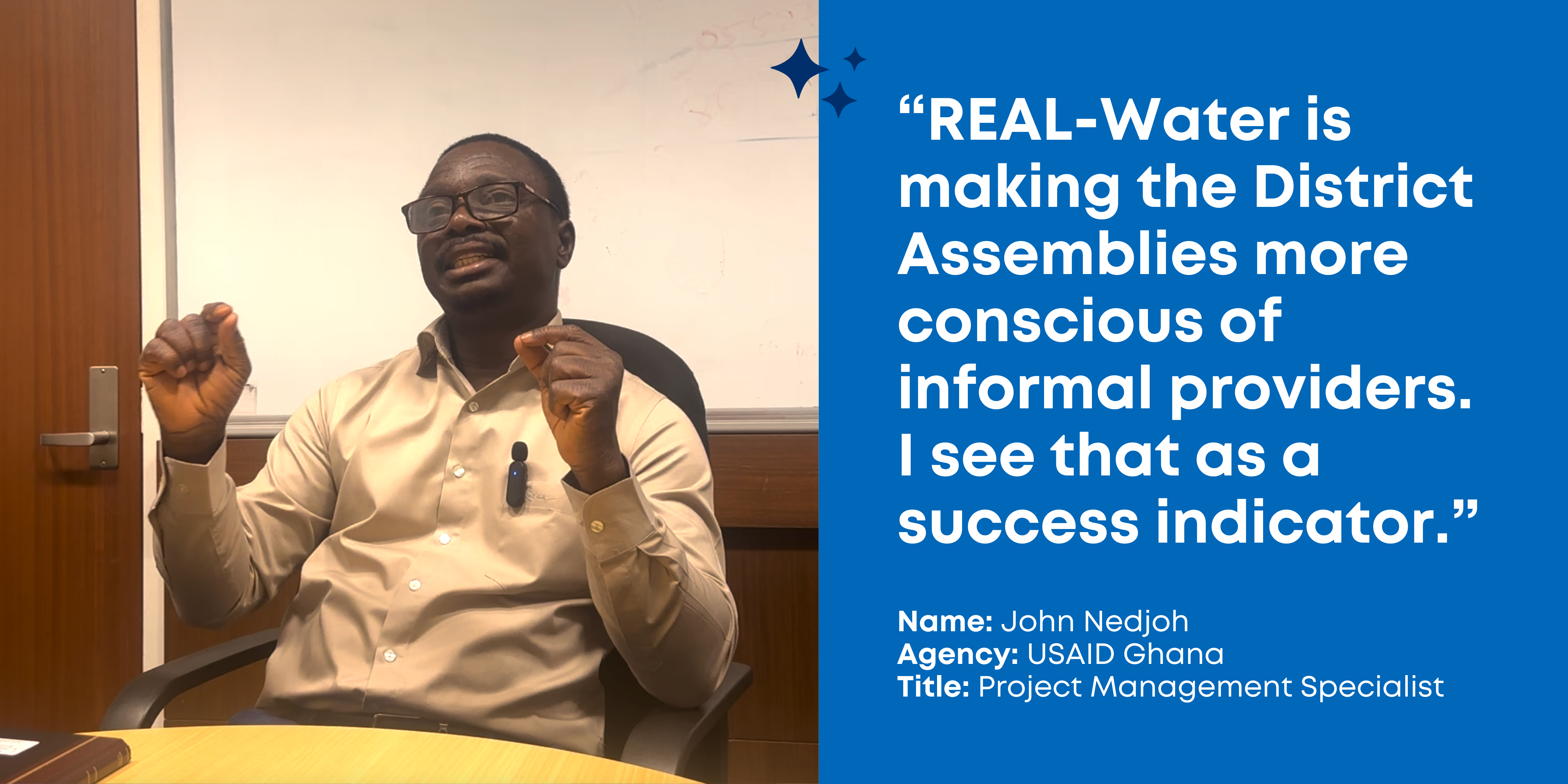

USAID has found that the Water Quality Assurance Fund program has made District Assemblies (the local government body responsible for water provider oversight) more aware of the prevalence of informal operators. As a result, District Assemblies have begun to identify and register informal operators with greater regularity.

The benefits of formalizing the sector are two-fold. First, it reduces tensions between formal and informal providers which result from the perceived ability of informal providers to set their own rates in contrast with regular suppliers who mostly follow government-approved tariffs. At the same time, registration fees and business taxes generate revenues for the local government.

Using their own resources, six District Assemblies in the Bono and Ahafo regions identified nearly 200 informal water operators, and around 40 percent of them have completed the formal registration process.

Some of the informal water operators who were unaware of the registration requirement now appear eager to register with local authorities and join the Assurance Fund program. But why would an informal provider choose to participate in the Fund and willingly submit to additional government oversight, extra paperwork, and fees?

USAID’s REAL-Water activity set out to answer this question. Here are three motivations they have found so far.

Motivation 1: Bridging Knowledge Gaps

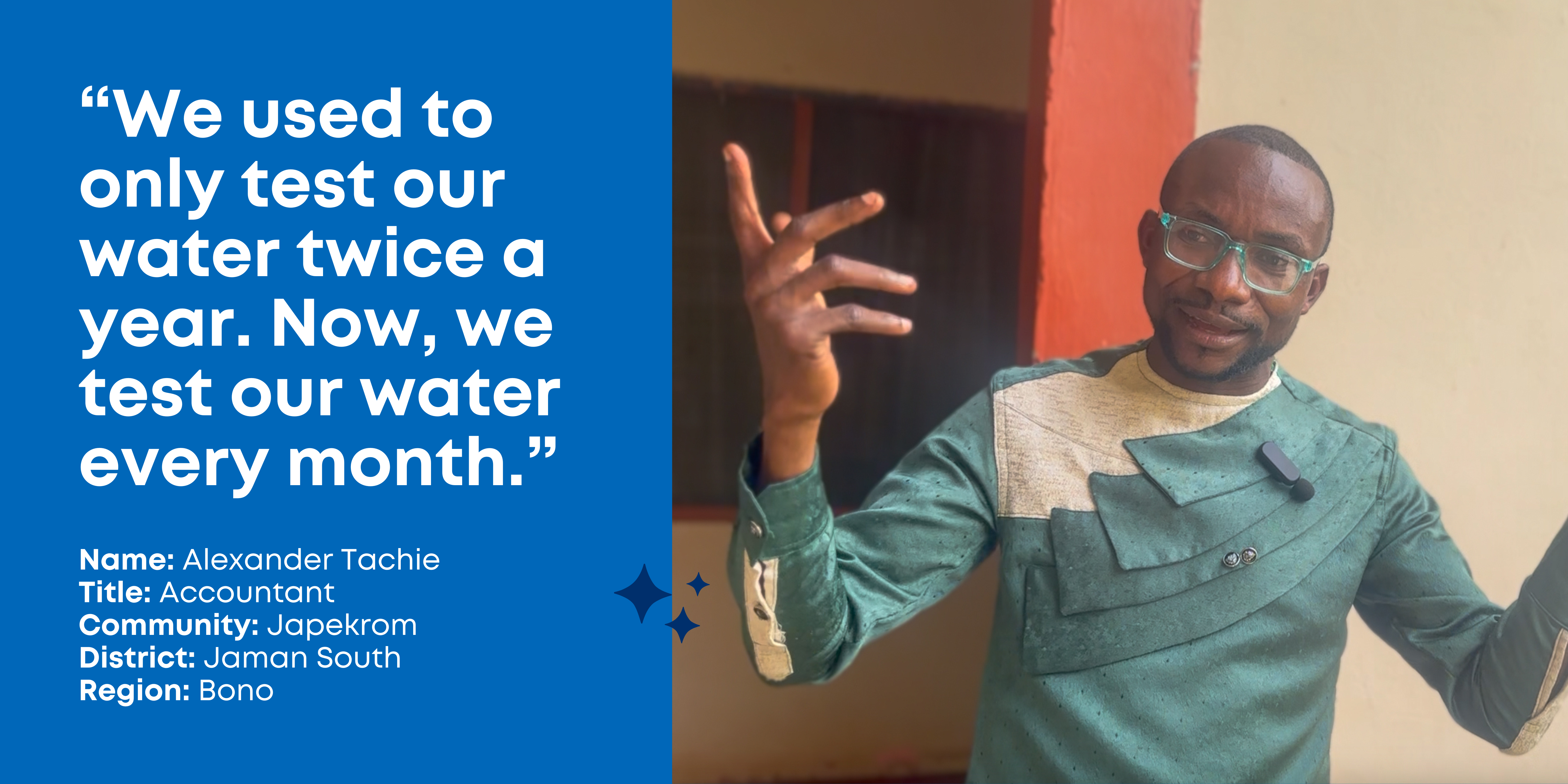

Inspired by the perceived initial successes of the Water Quality Assurance Fund, informal water suppliers told us that they became interested in accessing the Fund's financial and educational resources. It was also understood that participation in the Fund would increase recognition among customers and provide access to the Fund’s learning opportunities, such as monthly debrief meetings.

During the monthly assurance fund debrief meetings with water supply operators and the district assembly officials, participants compare water quality results and discuss water treatment methods and other water-related issues, such as how to keep your water points clean.

Since their involvement in the Fund, informal operators appear to realize the importance of water quality testing. “Before the Fund, I thought clean-looking water was safe water,” one operator admitted. Another informal operator expressed commitment to providing high-quality service to their community and family: “I drink this water,” underscoring a desire to build the confidence of customers in the community.

Motivation 2: Financial Impact

As consumers grasp the importance of water quality, their preferences may shift toward regulated suppliers who are known to test their water and who display test results in their offices.

Some District Assembly members and suppliers make the case that increasing the public awareness of water quality in the Fund study districts could influence consumers to prioritize suppliers who participate in the Fund, resulting in a loss of market share for those who do not participate.

This trend may gain further momentum as consumers replace bottled and sachet drinking water with less expensive public water supplies that are now monitored through the Assurance Fund. As the program becomes more widely known, it could transform the financial dynamics of water suppliers.

Motivation 3: Government Incentives

For District Assemblies, regulating informal water operators presents a dual benefit: it fulfills their mandate of overseeing water services and increases their revenue base. According to one District Assembly official, "We are partners in development, aiming to create an enabling environment for informal operators to thrive and complement the government's efforts in providing safe water.”

On the other hand, some informal operators indicated benefits of registration, beyond participation in the Assurance Fund evaluation, like receiving District Assembly support in obtaining permits, such as those required for water abstraction. While some District Assembly authorities have indicated willingness to apply pressure to informal suppliers to get them to register their businesses, it has not become necessary due to the benefits perceived by both parties.

All in Favor

This evaluation has increased the attention on informal water providers and driven an emerging consensus that both formal and informal water supply schemes are important parts of the water supply landscape in rural Ghana.

Increasingly, communities understand that the collaborative registration and enrollment of informal water operators in the Assurance Fund will improve water quality and, in turn, community health.

REAL-Water is collaborating with local authorities to explore ways of involving newly registered water suppliers. This includes considering a more active role for District Assemblies in coordinating water quality testing using urban laboratories. If the success of the Water Quality Assurance Fund proves a cost-effective intervention, the next step will be to consider the government’s role in expanding to more communities.

Related Resources

- USAID REAL-Water Explores the Impact of the Water Quality Assurance Fund on Ghana’s Water Sector Formalization

- Evaluating Water Quality Assurance Funds In Ghana: Baseline Assessment

- Implementation Manual: Water Quality Assurance Fund

- Emerging Trends in Rural Water Management

About The Author

Caroline Delaire leads a team of about ten staff members based in Ghana, Kenya, Uganda, and the United States as the Director of Research and Programs at Aquaya. She is responsible for ensuring the quality of research deliverables across the organization and for overseeing staffing, timelines, and budgets. Caroline has experience conducting applied research in the water and sanitation sector in sub-Saharan Africa, India, and Haiti. Caroline has a PhD and MS in civil and environmental engineering from the University of California, Berkeley, and an engineering diploma (BS and MS level) from the Ecole Polytechnique in France. She is a native French speaker.

About The Author

Vanessa Guenther is the Communications Manager at Aquaya. She leads communication and dissemination efforts to make Aquaya’s research more accessible. She shares Aquaya’s high-level outputs with international stakeholders and enhances analyses by developing user-friendly visuals. Vanessa builds Aquaya’s brand awareness through website, social media management, and search engine optimization. For the Rural Evidence and Learning for Water (REAL-Water) project, she coordinates communication outputs between consortium members and USAID. Vanessa has a MESM from the University of California, Santa Barbara, and a BA in strategic communication from the Hubbard School of Journalism at the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities. She is a native German speaker.

![Mumuni Abdul Wahab, a veterinarian, stands under a tree wearing a white polo shirt and gestures with his hands. "Seeing the [laboratory] trucks come by has increased confidence that water is safe for drinking." Asutifi North, Ahafo, Ghana](https://www.globalwaters.org/sites/default/files/6_0.png)

![Municipal Planning Officer, Franklin Walier, wears a traditional top with blue and white stripes and gestures with one index finger while speaking: "If you are an informal service provider and you don't take this opportunity to join [the WQAF], we will apply the law. You will risk your business." Asunafo North, Ahafo, Ghana](https://www.globalwaters.org/sites/default/files/8.png)

![Assembly member and water system manager, Paul Osei wears a yellow collared short-sleeved shirt and gestures with his hands: "All informal operators should be enrolled [in the WQAF] so that all providers can treat and test their water." Asunafo North, Ahafo](https://www.globalwaters.org/sites/default/files/12.png)