Searching for Sustained Water and Sanitation Improvements in Mozambique

Over the past five years, USAID commissioned six independent evaluations to take a close look at the legacy of USAID–funded water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) activities across the globe. Exploring how project interventions have fared anywhere from three to 10 years after closeout enables evaluators to gauge the staying power of project outcomes.

This final ex-post evaluation in the series examines the WASH component of the Strengthening Communities through Integrated Programming (SCIP) activity implemented from 2009–2015 in Zambézia Province, Mozambique. The evaluation’s findings raise questions about the behavior change approaches and tools used to achieve improved hygiene, the management structures put in place to sustain functioning water points, and the effectiveness of community-led total sanitation (CLTS) to move households up the sanitation ladder.

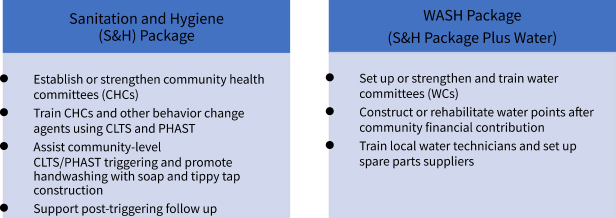

SCIP Zambézia designed WASH interventions to increase hygiene practices and use of clean water and sanitation facilities using CLTS and participatory hygiene and sanitation transformation (PHAST). Following a needs assessment, SCIP trained local entities to implement one of two intervention packages:

This evaluation assessed the sustainability of WASH outcomes in 239 communities four years after the activity ended. In August and September 2019, an evaluation team (ET) conducted 990 household surveys, including observations of 500 latrines and 822 handwashing stations; observed 46 water points (WPs), including water quality testing of 30 functional WPs; and completed 43 qualitative interviews with government officials, implementers, community health and water management committees, and community members.

What We Learned

Water point functionality and use: Four years after the activity ended, 65 percent of observed water points remained functional. Almost half of the water points tested positive for E. coli and 90 percent tested positive for fecal coliforms. This exposed communities to health risks, as only 16 percent of households reported treating their drinking water.

Water point management: Most WPs had active water management committees in place, and community members reported a high level of satisfaction with these committees. Sixty percent of respondents reported paying WP fees, which often proved insufficient to cover operation and maintenance costs. Fewer households below the poverty line made these contributions.

Sanitation quality and use: Fifty-two percent of households had access to a latrine, but only 15 percent had basic sanitation access, that is, access to an improved latrine that is not shared with other households. That level of basic sanitation was still higher than the 5 percent recorded at the activity’s (quasi-comparable) endline evaluation. Households below the national poverty line had significantly lower basic sanitation access than those above the poverty line. The evaluation team observed latrine quality as generally poor; only 23 percent of households had an observed slab. Respondents self-reported a low level of latrine use, and open defecation reportedly occurred in approximately 75 percent of the communities. Respondents reported financial and material barriers as the primary reasons they did not own a latrine. They aired frustrations about poor-quality materials leading to a continuous cycle of repair or replacement of latrines, especially after weather-related shocks.

Hygiene: Households reported high levels of handwashing with soap and water (64 percent); however, only 13 percent had observable soap and water. Of the 95 percent of households with a handwashing station, less than 2 percent had a fixed-in-place facility. The evaluation team rarely observed SCIP–promoted tippy taps, due to their reported lack of durability. Handwashing behavior did not appear to be normative.

Resilience: While SCIP did not directly seek to enhance resilience, the evaluation team did assess impacts of cyclones Idai and Kenneth and flooding, which affected roughly half of respondents’ WASH facilities. Replacement and repair of handwashing stations took place at a high rate. However, communities struggled to repair damaged water points; less than half of respondents reported resolution of issues several months later.

Why Does This Matter?

These results suggest a need to rethink several programming approaches. Understanding the long-term sustainability of USAID–supported WASH outcomes allows USAID and other stakeholders to identify challenges and best practices that can inform future programmatic strategies. This evaluation provides further evidence of persistent challenges with community-based water point management, including the sufficiency of fee collection, high rates of nonfunctionality, and accountability of government for water quality monitoring.

The overall poor sanitation indicators confirm other literature showing the traditional CLTS approach is not often effective in achieving sustained latrine use leading to the end of open defecation and is not well suited to prompt adoption of quality improvements up the sanitation ladder. Targeted sanitation subsidies, perhaps in combination with CLTS, have shown some promise for reaching the extreme poor and most vulnerable and merit further examination.

In line with current sector understanding, this evaluation further codifies that PHAST approaches to handwashing promotion, low-quality handwashing stations (e.g., tippy taps), and behavior change messaging alone are ineffective in fostering normative handwashing behavior in rural communities.

For more information, take a look at the full evaluation, the evaluation brief, the executive summary (Portuguese), or access other ex-post evaluations on Globalwaters.org.

By Holly Dentz, Senior Technical Specialist at USAID’s Water Communication and Knowledge Management project, and Abbie Jones, USAID Water and Sanitation Advisor