In a conservative society like South Sudan, menstruation is taboo. It is so taboo that mothers often do not discuss it with their daughters, and there are also significant social implications. Girls may face ridicule or abuse at school during their periods, and often have few available feminine hygiene products. In some rural communities, upon her first period, a girl is considered ready to marry, and can be forced by her family and community into a marriage she might not want. In other communities, research done by MOMENTUM Integrated Health Resilience has shown that a girl’s father or brother may beat her at the onset of menstruation, considering it a sign that the young woman has become sexually active. Along with work in communities to promote voluntary family planning and reproductive health, and efforts to strengthen health resilience in support of maternal, newborn, and child health, MOMENTUM works with community groups in South Sudan to address issues around gender and menstrual hygiene management.

Photo credit: Jacob Mogga

Girls themselves may not know which products to use during menstruation and, prior to MOMENTUM activities, there were high rates of infection among girls because they did not understand proper menstrual hygiene. As a result of the stigma and other implications of menstruation, girls can miss several days of school each month; one survey report found that over 60 percent of girls in South Sudan skip school for four to eight days during their menstrual periods.

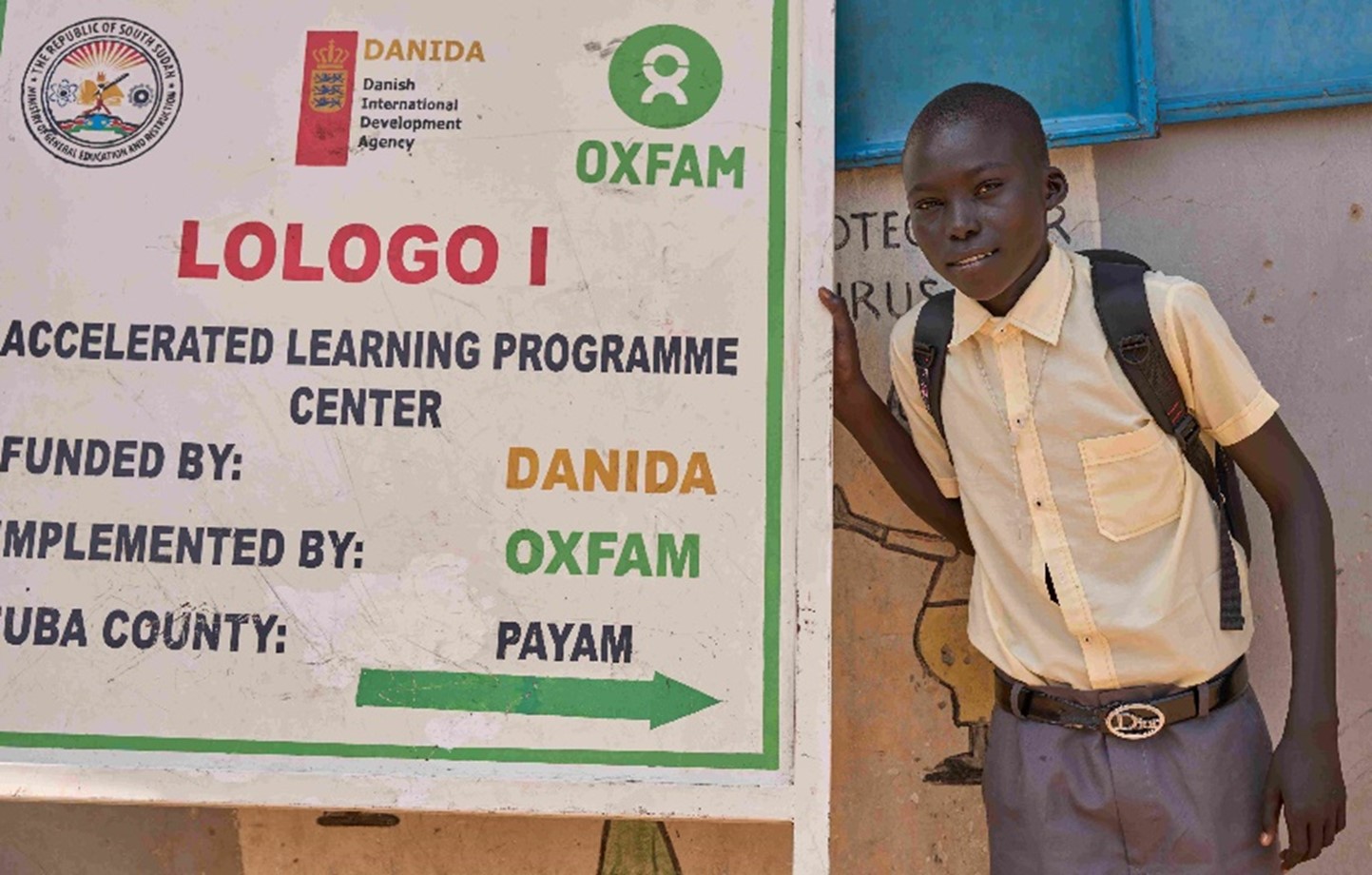

MOMENTUM has partnered with a local nongovernmental organization, The Rescue Initiative-South Sudan (TRI-SS), to develop community health and youth programming focused on voluntary family planning, reproductive health, gender-based violence, and related topics such as menstrual hygiene management. This partnership includes work with students and staff at Lologo 1 Primary Community School, a set of tightly packed cement block classrooms on the dusty outskirts of South Sudan’s capital city, Juba.

“These girls learn about menstruation from the school and older friends, not from their parents. But a senior woman teacher at this school had to talk with 261 girls about maintaining themselves during menstruation,” explained Harriet Fikira, Safeguarding and Sexual and Gender-Based Violence Officer with TRI-SS. “She didn’t have all the information and support she needed, so we talked to the male teachers to support her in talking to these girls. It’s an important issue because the school drop-out rates for girls after their first periods is very high.”

MOMENTUM and TRI-SS efforts in South Sudan align with several of USAID’s programmatic objectives and investments, including strengthening local partners, engaging local communities, supporting the health and dignity of women and girls, reducing child, early, and forced marriage, and addressing gender-based violence. But there are significant challenges, particularly for young women. For example, the average age at marriage for young women in South Sudan is 18.4 years, and South Sudan ranks second in gender-based violence prevalence in East Africa.

To help address the challenges, TRI-SS organized activities as part of the global Menstrual Hygiene Day (May 28, 2023) at Lologo Community School in coordination with the school and MOMENTUM. One activity was a brief role play involving a boy who gives a fellow student his sweater to wrap around her skirt after she has stained herself in class during her menstrual period. Despite the topic’s stigma, two brave students stepped forward from among their peers and volunteered to be at the center of the role play. The goal was to make the school’s students understand that this is just a normal part of life.

Julia Night, 18, is a tall, rather shy girl who is not immediately recognizable as a leader. But as the oldest of six children who lost their father, she has spent most of her life meeting challenges. When the request for a role player went out, she stepped up.

Photo credit: Jacob Mogga

“The other girls were afraid to play the role because menstruation is not openly talked about in my school and community. The girls thought it was embarrassing,” explains Julia. “I volunteered because I wanted the girls to know that periods are normal, and every girl must go through it.”

Steven Severio, 14, lives in the nearby community of Oruyia, and his daily walk to school takes about 45 minutes along irregular roadways and gullies. In his class of 100 students, he was the only boy to raise his hand when the role play leaders asked for volunteers.

“I did it to help my sister students,” says Steven, who is the second youngest of seven siblings. “I wanted to contribute, and I felt joy being on stage. The other boys learned about things that will be helpful to girls in the classroom. Things are harder for girls, especially because of the challenges around menstrual hygiene management.”

Photo credit: Jacob Mogga

“The boys laughed at me when I was preparing to play the role,” sighed Julia. “But my role made the boys understand that it’s normal for girls to menstruate, and they must support the girls who are menstruating. Boys must know that our bodies go through changes and they must help the young girls who menstruate and stain themselves; the boys should also talk about menstruation to other boys.”

Photo credit: Harriet Fikira, TRI-SS

“We reached 200 pupils that day with awareness messages on menstrual hygiene management,” said Leyaa Nejuwa, Social and Behavioral Change Officer with TRI-SS. “Role plays reinforced the messaging, and then we gathered feedback from the audience.”

It seems the messages were embraced by students. Charles Obura Martisio, the school headmaster who also manages a classroom of 60 students, has noticed a difference in behavior since the role play and related lessons: “Girls have stopped missing school due to menstruation.”

The school actions sponsored by TRI-SS and MOMENTUM are part of a larger community strategy to engage parents and their daughters, and to build relevant peer-to-peer awareness and support among males.

During community meetings, parents said they learned about menstruation from other peers as they were growing up, so they do not know how to start talking to their daughters, according to Harriet Fikira of TRI-SS. Parents do say they are willing to support their children, ensure that girls complete their education, and provide pads and talk to them about menstruation at home. Harriet says she is grateful about the positive changes that they are seeing in the community because of the partnership with MOMENTUM.

The efforts also reach MOMENTUM’s goal of strengthening health resilience. As communities learn to understand the best practices for young women during menstruation, sanitation will improve. The community school also did not have proper toilet facilities for the girls, and this is being addressed.

Photo credit: Jacob Mogga

“Prior to the role play, I did not understand the effect that menstruation had on girls’ education, and I wondered why my fellow female students were frequently absent from school,” explains Steven, who wants to be a mechanical engineer someday because he likes trying to repair cars. “I hope that boys will help girls and be understanding instead of bullying them. If boys and girls work together, we will all be happier.”

Photo credit: Jacob Mogga

Challenges remain, such as unclean toilet blocks without any water to wash up.

“I hope that girls can get supported and menstruation is looked at as a normal thing. The boys can pass the message to the other people to create change in the community,” concluded Julia.

*This blog was originally published on USAID MOMENTUM on January 2, 2024.