20 Seconds That Save Lives: Prioritizing Water & Hygiene to Fight COVID-19

This story originally appeared on Agrilinks.org

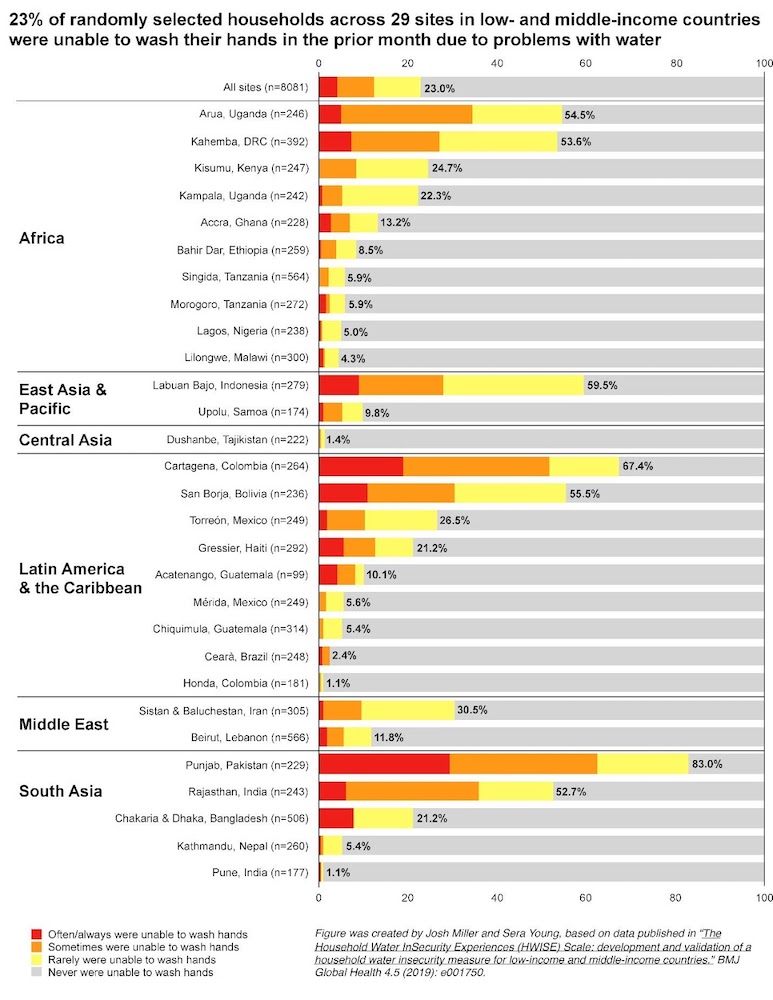

Hand washing with soap and water for at least 20 seconds — coupled with social distancing, wearing face masks, and testing — is currently the most effective tool available for preventing and controlling the spread of COVID-19 amongst all segments of a population. However, according to the Joint Monitoring Programme for WASH, over three billion people worldwide lack hand hygiene facilities at home, and four in ten health care facilities lack hand washing stations with soap and water or alcohol-based hand sanitizer at points of care. Furthermore, 29% of the global population does not have access to water at home to enable hygiene behaviors. Whatever water they do acquire for their households takes time and effort, and the various uses, such as drinking, cooking and washing, must be prioritized. Significant inequalities between the wealthiest and poorest quintiles and between rural and urban areas persist in access to water, sanitation, and hygiene. This leaves large portions of the global population, particularly health care workers and those most vulnerable and marginalized, extremely susceptible to the pandemic currently facing us all.

For those currently lacking access to safe drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH), other health conditions — particularly chronic or acute diarrhea or other water-borne illnesses — may be an ongoing concern. Diarrhea can contribute to malnutrition, particularly in children under five years old — which, in turn, can weaken the immune system and potentially increase risk of co-infection during an infectious disease pandemic.

A strong, inclusive policy framework and sufficient financial and human resources are key to ensuring that strong, resilient WASH services are in place. Despite the fact that 79% of countries surveyed for WHO’s annual Global Analysis and Assessment of Sanitation and Drinking Water (GLAAS) indicate that they have a national WASH policy that includes hygiene, only 9% report having sufficient financing to implement their plans.

Where WASH, especially water and hygiene supplies and facilities, is unavailable or unaffordable, the ability to prevent the spread of COVID-19 is compromised. This impacts other sectors as well, such as food systems in low-income countries where markets and small food enterprises operate in clusters and in close quarters, making the availability of water to enable hand-washing in those locations critical to preventing both COVID-19 and hunger. Closing the hygiene financing gap as well as strengthening national WASH plans requires elevating the voices of those currently excluded from access to WASH, and improving the capacity of the policy system to include and respond to those voices.

The lessons of COVID-19 so far echo those from West Africa’s Ebola outbreak in 2012: investment in WASH is investment in public health. However, the trajectory of COVID-19 appears to be closer to that of HIV than Ebola: the impacts of this pandemic are wide-reaching across society, the economy, and public health, and responses must occur at the systems level and focus on equity and sustainable impact. Approaches that target only health facilities or populations already directly affected by the virus will not be sufficient to prevent large-scale infections or to prevent endemicity. Where existing water and sanitation systems are compromised due to workers being reprioritized or sent home, lost revenue from missed customer payments or other challenges linked to the pandemic response, recovery will be more difficult. As the global community continues to grapple with how best to ensure that everyone, everywhere, has the water and soap needed to wash their hands to prevent the spread of COVID-19 now, we must also look ahead to the risk of reduced access to water and sanitation in the future, as limited resources are redirected towards other priorities. Doing so without simultaneously focusing on policy, governance systems, and inclusion will leave us no better prepared when the next pandemic strikes.

By Lisa Schechtman, USAID Bureau for Resilience and Food Security; Jesse Shapiro, USAID Bureau for Global Health; and Oliver Subasinghe, USAID RFS.